1888, April 6: Curses of the Ingram Mummy

In an 1896 issue of The Strand magazine of London, England, an extraordinary tale was told about the final fate of Herbert Ingram, who had assisted Lord Charles Beresford in the 1884-1885 Soudan War.

Ingram had taken his own steam launch out to Egypt to volunteer for the Gorden Relief Expedition which was to travel up the Nile to assist British forces trapped in Khartoum. As a sort of souvenir of his Egyptian adventures, Ingram bought a mummy for £50 from the English Consul at Luxor, and had it shipped home from Cairo.

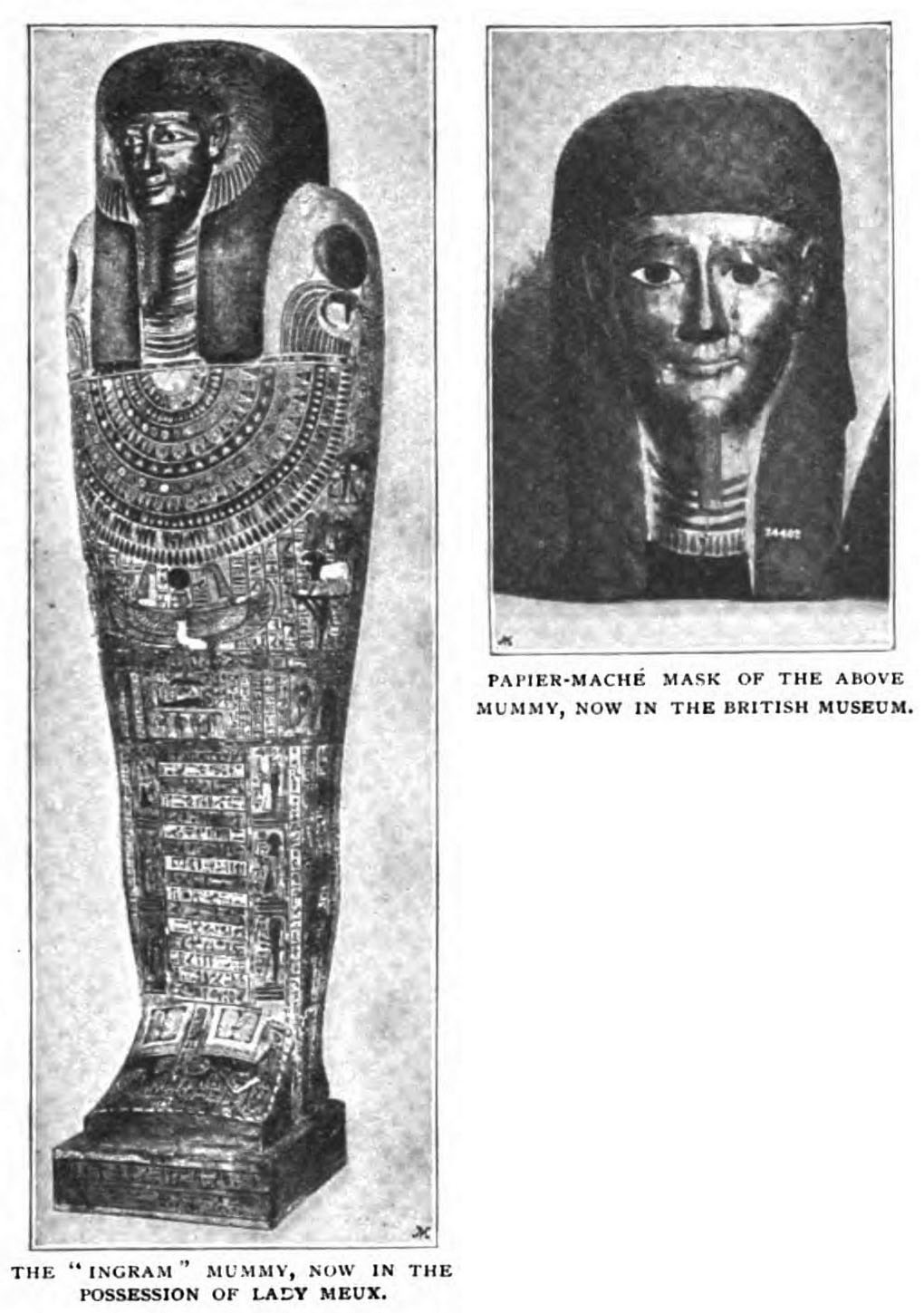

The Ingram Mummy, ca. 1888. [Larger version here]

The mummy was that of a priest of Thetis, and a representative from the British Museum was asked to decipher and translate the inscriptions on the mummy's case. The inscription set forth that whosoever disturbed the body of this priest should himself be deprived of decent burial: he would meet with a violent death, and his mangled remains would be "carried down by a rush of waters to the sea." The curse was found to be amusing, and soon forgotten.

Some time after sending the mummy home, Mr. Ingram and Sir Henry Meux were elephant-shooting in Somaliland, when one day the natives brought in a great chunk of dried earth, saying it was the spoor of the biggest elephant in the world. The temptation was too much for the two sportsmen, so they tracked the elephants. When they spotted the herd, Sir Henry realized he had left his elephant gun back at the camp; Ingram graciously offered his own gun for the knight to use, leaving himself with a comparatively impotent small-bore rifle. While Sir Henry followed the bull of the herd, Ingram focused on downing one of the cows. By galloping his horse by the elephant, he was able to shoot and run away, so as to hopefully take her down with a large number of small shots... but as he was watching the elephant and not his course, he was swept from his saddle by the drooping bough of a tree. The wounded elephant was on him almost the very moment he hit the ground, and Ingram was trampled to death despite his Somali servant shooting the elephant in the ear with his rifle.

For days the elephant would let no one approach the spot, but eventually Mr. Ingram's remains were reverently gathered up and buried for the time being in a ravine. However, the body was never seen again for, when an expedition was afterwards dispatched to the spot, only one sock and part of a human bone were found; these pitiful relics were subsequently interred at Aden with military honors. It was discovered later that the floods caused by heavy rains had washed away Mr. Ingram's remains, thereby fulfilling the ancient prophecy — the awful threat of the priest of Thetis.

The author of the article then informed his readers that the mummy was now in the possession of Lady Valerie Meux, and that her husband, Sir Harry, had the tusks of the elephant that killed Ingram.

Right and Wrong

The Strand magazine appears to be the earliest printing of the account... and where everyone else got it from. The article is a twelve-page, illustrated interview with Lord Charles Beresford [1846-1919], and the brief account of Ingram's death and the circumstances around it fill a page and a half. The details were supplied to the author by both Lord Beresford and by Sir William Ingram [1847-1924], brother to the deceased man; and Lord Beresford later repeated the story in 1914 when he published his memoirs. All of which is odd, by the way, because anyone who took a moment to research it would have found one big problem with the story as it exists.

Lieutenant Walter Herbert Ingram, son of the Herbert Ingram who founded the London Illustrated News and who was often also called 'Herbert' (apparently) did in fact find and bring home a mummy from Egypt. Later in life... as in several years later... he was in fact trampled to death, on April 6, 1888, by an elephant which then stood near his body for several days, and his body was indeed buried in a shallow place and subsequently washed away. Ingram had given the mummy to Lady Meux in 1886... two years before he was trampled to death. The supposed curse of the mummy was only mentioned in print after his spectacular death.

It is unlikely that a curse was ever presented to Ingram or anyone he knew before his death, because the representative from the British Museum would likely have been their resident Egyptologist at the time, Dr. E.A. Wallis Budge. Though Budge didn't print anything about any initial examination of the mummy, after Lady Meux received the mummy from Ingram, she allowed Dr. Budge to do a full inspection of it. Dr. Budge published a translation of all of the hieroglyphics on the case and mummy itself in 1893... three years before The Strand published the story of the mummy's curse. Budge's translation gave the mummy's name as Nes-Amsu, second prophet of the god Amsu, and showed that the mummy's case had many classic exhortations to the gods of Egypt to recognize Nes-Amsu as a good man and to help him find a good place in the afterlife... but it doesn't contain any form of curse aimed at those who touch his body.

So, in short, two years after Walter Ingram gave the mummy to Lady Meux, he was trampled to death while hunting with her husband; and this was blamed on a curse that didn't exist on the case of the mummy Lady Meux possessed. I mean, really, after two years with the mummy, you'd have expected Sir Henry and Lady Meux to have been victims if there was a curse, right?

Oops.

Spoke too soon.

The Legend... What, AGAIN?!?

In early to mid 1911, newspapers worldwide carried the new 'true story' of the curse of the mummy of Nes-Amsu. Lady Meux had died on December 20, 1910, and, among other interesting clauses in her last will and testament, she bequeathed her extensive collection of Egyptian antiquities -- over 1,700 objects in all -- to the British Museum with the stipulation that they must take the whole collection, or none of it (it was to be sold off as separate pieces if they chose not to accept). Presumably, Dr. Budge was thrilled; he still worked as the head of the Egyptian antiquities department at the museum. The newspapers, however, asserted that "believers in the supernatural" were concerned about what would happen to the institution if it took the cursed mummy of Nes-Amsu into its collection.

The story of the mummy's curse was repeated in the newspapers, lest anyone doubt the danger... of course, it was a different story than the previous one, but few likely noticed.

In this new story, the mummy was first acquired by Walter Ingram, who bought it while serving in one of the Nile campaigns... due to a misunderstanding, Ingram had paid the dealer less than was expected, and in his wrath the dealer had heaped an ancient curse upon Ingram's head. After the mummy was brought to England, Ingram gave it to Lady Meux for her growing collection of Egyptian antiquities; and when the hieroglyphics on the case were translated, they were found to contain the following curse: "If any person of any foreign country, whether he be black man, or Ethiopian, or Syrian, carry away this writing, or it be stolen by a thief, then whosoever does this, no offering shall be presented to their souls, they shall never enjoy a draught of cool water, they shall never more breathe the air, no son and no daughter shall arise from their seed, their name shall be remembered no longer upon earth, and most assuredly they shall never see the beams of the Disc..." i.e. the Sun God1.

Naturally, Ingram's death by elephant attack two years later was then implied to have been due to either the mummy's new curse, or the Egyptian dealer's uttered curse (take your pick!). In addition it was pointed out that when Sir Henry Meux died in 1900, it brought the Meux Baronetcy to an end for he and the Lady Meux had never had children, "another clause of the curse therefore being fulfilled." So, naturally, it was expected that the curse -- which for some reason still wasn't in Budge's translation of the hieroglyphics, and somehow let Lady Meux live for twenty-four years -- would be bad luck for the British Museum when they inheirited the mummy.

Nobody had to worry, however... for reasons never stated, the trustees of the British Museum decided to decline the bequest, and so Lady Meux's collection was put up for auction and sold piece by piece instead. Still the newspapers warned prospective buyers of the newly updated curse, only now it was claimed that the new translation was from a papyrus buried with the mummy, and not from the mummy itself or its case. It was also implied by at least one paper that Ingram may have given the mummy to Lady Meux in an attempt to pass the curse to someone else before it hit him. The warnings didn't prevent Nes-Amsu from being sold at auction to an unknown buyer, and the current whereabouts of the mummy are unknown... luckily, Budge made and published his study of the artifact before it vanished into a private collection2.

The legend got one more boost before it finally, quietly, was forgotten. On May 14, 1925, Henry Rider Haggard passed away at the age of 68. Haggard was the well-known author and creator of such memorable characters as the African adventurer Allan Quatermain and the enigmatic Ayesha, also known just as "She." About a year after his death, Haggard's memoirs -- Days of My Life -- was published in both book form, and serialized in The Strand Magazine of London. One of Haggard's best friends was none other than Dr. E.A. Wallis Budge of the British Museum, to whom Haggard had dedicated one of his earlier books, Morning Star. Being that Haggard couldn't resist a good story, and that a good story had already attached itself to Budge, it was natural that Haggard would have to at least mention the mummy. After summing up the basic details of the events above, Haggard wrote that he had asked Budge if he believed in curses:

"He hesitated to answer. At length he said that in the East men believed that curses took effect, and that he had always avoided driving a native to curse him. A curse launched into the air was bound to have an effect if coupled with the name of God, either on the person cursed or on the curser. Budge mentioned the case of Palmer, who cursed an Arab of Sinai, and the natives turned the curse on him by throwing him and his companions down a precipice, and they were dashed to pieces. Budge added: 'I have cursed the fathers and female ancestors of many a man, but I have always feared to curse a man himself.3"

NOTES

- I initially thought the new curse was entirely a creation of the newspaper writers, but I recently ran across something interesting while researching a related story. Dr. Budge published Babylonian Life and History in 1886, which contained many translations of Assyrian texts as part of his explanation of the known history of the Babylonian culture... and one of these translations contains a curse that is verbally similar to what the newspapers attributed to Nes-Amsu's mummy as the new curse. From an inscription dated B.C.1330 that describes a ruler's accomplishments, we read "...mightily may they injure him, and with a grievous curse quickly may they curse him; his name, his seed, his forces and his family in the land may they destroy..." So now it seems that the new curse was penned, at least in part, by someone who read Budge's book on the Babylonians!

- A gentleman named Paul Broughton has been trying to track down Nes-Amsu's missing mummy, and suspects that it was bought by William Randolph Hearst, who bought a great number of the other pieces in the Meux auction. Read his brief post at the Egyptology News Network.

- The contents of Henry Rider Haggard's memoirs had been shown to a number of people for their approval before publication, with the additional hope that some of them would add personal experiences about Haggard to the final book. One of the people who saw the text before it was published was Dr. Budge, who was still alive. So, by inference, the text about the Ingram mummy and it's curse, as well as Budge's own quoted comments about the validity of curses, were looked at and approved by Dr. Budge himself before publication!

Anomalies -- the Strange & Unexplained, as well as my other website -- Monsters Here & There -- are supported by patrons, people like you! All new Anomalies articles are now posted for my patrons only, along with exclusive content made just for them. You can become a patron for just $1 a month!

|